FTM / Energy Innovation / Vishay — Thermistor Simulation

The suggestion that a design engineer should perform electronic circuit simulation can be controversial. It is often argued that the software is too expensive; that simulation times are too long; that simulation does not properly account for parasitic effects such as temperature variations and product tolerances; and that the results simply do not represent very well a very complex reality.

This article tests these objections in the context of a real-world example: the simulation of a pre-charge circuit for automotive battery chargers. The circuit contains a network of Vishay PTCEL67 thermistors/inrush current limiters. The simulation is run on the Qorvo QSPICE® software tool.

The pre-charge circuit

Qorvo’s QSPICE simulator is free to use without any restrictions: this neutralizes the common objection that simulation software is too expensive.

After installing the software, the engineer will need good models for Vishay’s ceramic-based PTCEL67: these are available on Hackster.io. Not only are the models available for download, but engineers can also perform a full simulation of the charging of a capacitor by a rectified ac mains network through a network of PTCEL67 devices.

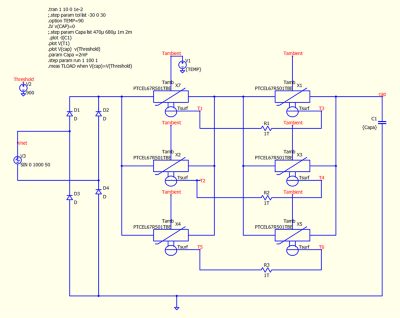

Such a circuit is demonstrated in Figure 1, which shows the rectification of a 50Hz, 1,000V ac voltage with a diode bridge and a 2mF capacitor. Surge current limiting and thermal protection are provided by a network of six PTCEL67R501TBE thermistors, comprised of three parallel branches of two elements in series.

For illustration, it is possible to replace the PTCEL network with a fixed equivalent resistor of 333Ω, as three parallel branches of 2 x 500Ω, and simulate the time it takes for the capacitor to reach 90% of its final voltage: this is 4.755s. This value gives us a reference point for our later simulations.

It is also easy to verify that with an ac mains power supply, the capacitor charging-time constant of 63.2% is higher than the dc mains RC constant, 333 x 2 x 1E-6 = 0.67s. With an ac mains power supply, the time constant for 63% is in fact equal to 2.08 x RC = 1.387s.

Fig. 1: Pre-charge circuit for a capacitor with an 1,000V ac mains power supply

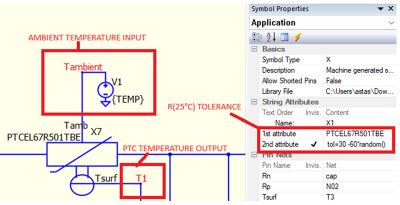

Temperature and tolerance

The PTCEL67R501TBE model used for this simulation takes into account variation in ambient temperature via the Tambient node, shown in Figure 2. It also shows the self-heating above this temperature via the Tsurf node. The last Tsurf pin can be used to connect the PTCEL thermistors if the user decides to thermally link them.

In Figure 1, resistances R1, R2, and R3 do not refer to electrical resistances, but thermal resistances, expressed in °C/kW. This is an electronic representation of the thermal conduction performed, for example, by a thermoconductive silicon paste deposited on the serial PTCEL components, which then have to be pressed against each other on the board. In the schematic shown in Figure 1, these resistances are of about 1T: in this case, the serial PTCEL devices are not in contact with each other.

Finally, the electrical R25 tolerance of the PTCEL67R501TB0 of 500Ω ±30% is denoted as TOL, and is evaluated in a random way by means of the product attribute:

TOL = 30 -60*random()

where random() changes from 0 to 1.

With the issue of parasitic effects now handled, it is time to run the simulation.

Fig. 2: The tolerance and temperature properties of the PTCEL model

The simulation

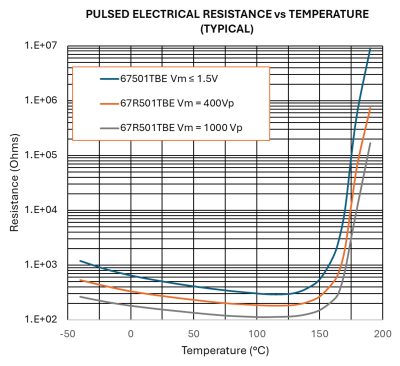

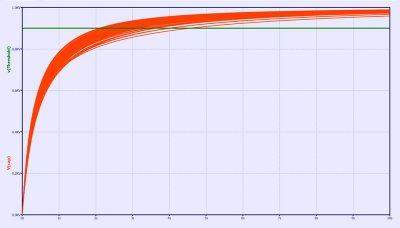

The capacitor must be charged at a minimum of 900V within a 4s delay. As already established, with a fixed resistor the charge time would be 4.755s. But as the resistance of the PTCEL decreases when voltage is applied, and as its temperature increases prior to the switch, as shown in Figure 3, the desired result of 4s is still possible.

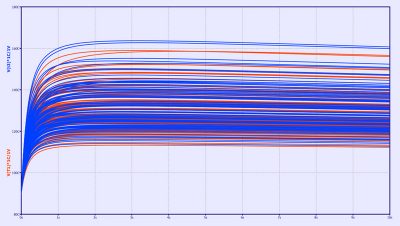

Plots are shown for the voltage rising at the capacitor, in Figure 4, the temperature variation of two PTCEL67 thermistors in series in one parallel branch, in Figure 5, and the inrush current into the circuit, in Figure 6.

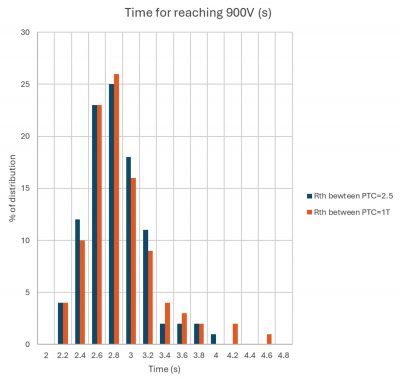

A .meas SPICE directive is used to compute the time needed for the capacitor voltage to reach 900V from 0V. A total of 100 simulations are made, with the TOL changing randomly for each PTCEL independently of each other. The results are then plotted in the histogram in Figure 7.

Fig. 3: PTCEL resistance variation as a function of temperature, in pulsed voltage

Fig. 4: Capacitor voltage drop for the circuit in Figure 1

Fig. 5: The temperature change of two PTCEL67 placed in series in one branch

Fig. 6: Variation of the capacitor current over time

Fig. 7: Histogram of the distribution of the time for the capacitor voltage to reach 900V

The results

The histogram in Figure 7 shows that in a small proportion of cases, charging takes longer than the 4s target. This happens because of the ±3% tolerance in the PTCEL’s R25 characteristic. As a result, some units switch faster, which increases the global network resistance and thus the charging time.

To correct this effect, the engineer can increase the thermal efficiency of the PTCEL67 network by thermally connecting both PTCEL67 thermistors in each parallel branch. This dramatically decreases the R1, R2, and R3 values to 2.5°C/W.

Fig 8: Histogram of the distribution of the time for the voltage capacitor to reach 900V after reducing the thermal resistance of the PTCEL67 thermistors

A repeat of the Monte Carlo simulations shows that the thermal connections between the PTCEL units decreases the spread, so that the worst-case time to reach 900V falls just below 4s. Thermal contact equalizes the temperature of the PTCEL units in each parallel branch, suppressing the distribution tail. Of course, this simulation result does not exclude the possibility that the 4s time will be exceeded in marginal cases: more simulations would be needed to assess the absolute maximum time value.

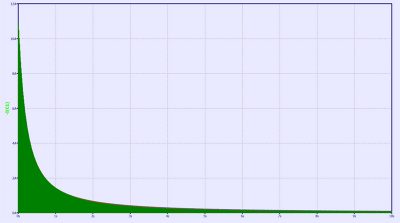

One objection to simulation raised above was that simulation takes too long: Figure 9 shows that each of the hundred simulations was performed in less than 2s. This is incredibly fast, and gives QSPICE users the option to increase the number of runs.

Fig. 9: Simulation time for the circuit in Figure 1

Simulation vs reality: a judgment call

Now that no-nonsense results have been reached using free software, taking temperature and tolerance effects into account, within a reasonable time, one question remains open: whether these results are representative of the real world. This is a decision for each engineer to take for themselves.

My recommendation is to practise the simulation first with a real application, which might be much more complex than the one studied in this article, using Vishay SPICE models and QSPICE software from Qorvo: check whether real-world results match the simulation outputs provided here.

Then make a determination whether the QSPICE software, with Vishay SPICE models from Hackster.io, predict reality. Given the care which was taken in the building of the SPICE models, and the power of QSPICE to achieve accurate results, I have very little doubt that simulation and reality will align.